Author: Josh Fenton

Bregenz is a small and quiet city. By day people go about their business in no particular rush and by night the civic spaces display a certain repose. In these after dark moments, even spaces that generally tend to be characterised by the uproar of youth such as skate parks and alleyways, are hushed. It is as though some external force leads their inaction.

It is from this zone of quiet that we move into Susan Phillipsz’s latest sound work Night and Fog (2016).1 The arrangement of the Kunsthaus Bregenz, as designed by Peter Zumthor means that there is no vestibule, or space of transition. The Listener moves directly into the acoustic arena of the work. The action performed here by Phillipsz is the inhabitation of an entire building, a similar strategy to that employed at the K21, Dusseldorf, for The Missing String (2013). 2 On the floor of entry the viewer is presented with neither image nor text, instead we hear the low resonant notes of the bass clarinet, loosely working through a melody. There is a sense that though there is chordal progression, the resolution is never obtained.

In the press release material for the Night and Fog installation Phillipsz highlights the intentional ‘gaps and spaces where the other instruments should be’3. In the gallery, these gaps are heard as pregnant pauses, in which the listener is unsure if the piece has reached its point of conclusion. In these first in-between moments the cutting sound of shoe soles on the polished concrete floor penetrates the silences; rather than an exchange between the four musical voices, as is heard on the upper levels. [Sound Clip 1]

In the press release material for the Night and Fog installation Phillipsz highlights the intentional ‘gaps and spaces where the other instruments should be’3. In the gallery, these gaps are heard as pregnant pauses, in which the listener is unsure if the piece has reached its point of conclusion. In these first in-between moments the cutting sound of shoe soles on the polished concrete floor penetrates the silences; rather than an exchange between the four musical voices, as is heard on the upper levels. [Sound Clip 1]

The fifth musical voice is isolated from the main body at the Kunsthaus Bregenz. Phillipsz introduces the flute through a satellite installation in the Hohenems Jewish Cemetery. There is metaphorical significance in this dismembering, referring back to the displacement and distress documented in Alain Resnais film Nuit et Brouillard (1957), the point of departure for this work. 4 Resnais’ work, which candidly documents the treatment and gradual dehumanization of the Jewish peoples in Nazi Concentration camps is paired with a score by Hans Eisler, which Phillipsz fragments in this work.

The distance Hohenems and Bregenz is stressed in the audible absence of the other voices. The pauses again form ‘non-silences’ in which one finds the details of that particular place. The semi-rural location is relatively still, but we search through the details, identifying and categorizing. Our ears become the ‘aggressively seeking mechanisms’ that Juhani Pallasma writes of, rather than ‘passive receivers’. 5 We seek out the minutiae: of the bird calls, our footsteps, and our breath. The recording methodology, whether by chance or intent, has redefined our acoustic sphere. Standing in the correct position on site we are able to hear the flautist’s intake of breath, our ‘organ of hearing’ is finely tuned to the extrasensory. This audible breathing action transforms the experience into event, an event in which we question our scale in relation to the soundscape. ‘The lungs that would produce such a volume must be large…’ we find ourselves questioning, ‘and what of body that holds them?’ The absent performer enlarges himself, drifting above the cemetery, inhabiting both the fog and the tree canopy overhead.

Jan Verwoert highlights the human expression of the sounds in Phillipsz’s The Missing String. In the cemetery also, the sounds are separated from the machine of the orchestra with its ‘weight and power’ and as such the performance is much more intimate. 6 This intimacy creates a duality in our relationship with the piece. In the first instance, the listener initiates the performance through a rudimentary switch at the cemetery gate, and posits themselves as the sole patron of the piece. The listener is like a child with a music box, sounds intimated to them in the private confines of their bedroom (cemetery walls). In the second instance the listener is an eavesdropper. Like the King’s spies in A King Listens, who are ‘stationed behind every drapery, curtain, arras’ we too are stationed behind the cemetery walls listening to the sounds beyond. 7 Sound Practitioner David Toop also draws reference to this duality, writing that ‘[e]ither we experience scenes at a distance, in which we have no overt part, or we are directly addressed […] often the relationship fluctuates, or is maintained at two levels simultaneously. 8

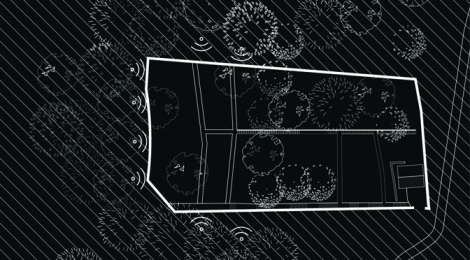

Though silence is evidently hard to control, there is a notion that its incorporation into a sound work or piece of music allows the performer or artist a level of authority over the listener. In Anti-Self: Experience – Less Noise, the GegenSichKollektiv, write of how silence becomes an ‘enveloping conceptual framework’ which as an aesthetic tool ‘subjugates the opportunity to reflect on the reality of sound in this context’. 9 This notion of subtle control can be seen in Night and Fog in the way that silences are used in combination with spatialisation. In the Kunsthaus the close grid arrangement of the loudspeakers reduces our understanding of sound to general direction and pitch, timbre and duration are lost in the confusion of transmission. Silences become moments of seeking out what has gone before. This contrasts with the arrangement at the cemetery installation, where the loudspeakers are spaced at large regular intervals along the boundary wall of the cemetery allowing clear separation of each component voice. In this setting the silences become moments of expectant waiting, for the resounding of a specific voice.

In this experience of space Phillipsz becomes the puppeteer, crafting, directing and managing the performance from every angle. The boundary formed by the cemetery walls is made much more prominent through Phillipsz’s use of sound and the absence of sound. As such Phillipsz’s work points us towards sound rather than image as the key driver of our understanding of space. The audience is able to use sound as a means of measuring distance and as a point of mediation between the listener and performer.

1 Rudolf Sagmeister, Curator. Susan Phillipsz, Night and Fog (30.01.16 – 03.04.2016) Kunsthaus Bregenz, Bregenz, Austria.

2 Florence Thurmes and Ansgar Lorenz, Curators. Susan Phillipsz, The Missing String (09.11.13 – 06.04.14) K21, Düsseldorf, Germany.

3 Thomas D. Trummer, Susan Phillipsz: Night and Fog – Anna-Sophie Berger: KUB Billboards, 8

4 Filmed largely in 1955 at several camps in Poland, Nuit et Brouillard also combines archival footage and film stills. The documentary is presented alongside Susan Phillipsz exhibition in the Kunsthaus Bregenz.

5 Pallasma, The Eyes of the Skin, 41.

6 Jan Verwoert, ‘Adversity’ in Susan Phillipsz: The Missing String, ed. Amsgar Lorenz, Florence Thurmes (Dusseldorf: Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, 2013), 72.

7 Calvino, ‘A King Listens’ in Under the Jaguar Sun, 39.

8 Toop, Sinister Resonance: The Mediumship of the Listener, 83.

9 Gegensichkollektiv, ‘Anti-Self: Experience-Less Noise’ in Reverberations: The philosophy, aesthetics and politics of noise, edited by Benjamin Halligan et al. (London: Continuum Intl Pub Group, 2012), 194 – 206.